LITERATURE - 2016, Journal of Hungarian Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Histological types of ovarian cancer in Arad county: a fifteen years retrospective analysis

Authors: Furău Gheorghe MD1, Furău Cristian MD1, Daşcău Voicu MD1, Dimitriu Mihai MD2, Păiuşan Lucian MD1

1”Vasile Goldiş” Western University of Arad, Romania,

2“Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania

Objectives: The purpose of this study is to examine the histological types of ovarian cancer in Arad County during 1998–2012. Materials and methods: The data were collected from the Histopathology Exams (HPE) registers and were retrospectively analyzed and compared with international database using GraphPad Software and Epi Info 7.

Results: Ovarian cancer was discovered in 118 cases, representing 6.73% of all genital cancers (1754 cases). There were 112 cases of primary cancer (94.92%) and five cases of ovarian metastatic cancer (4.24%), one patient having a combination of the two (0.85%). Different histological types of carcinoma were detected in 105 cases of the 113 primary cancer cases, who had 118 histological types (88.98% of the histological types), yolk sac tumors, tumors of the granulosa, immature teratoma, and disgerminoma in three cases each (2.54% each), and Sertoli–Leydig tumors in one case (0.85%). Five (2.56%) had an association of two cancer types (yolk sac tumor with embryonal carcinoma, immature teratoma with neuroepithelial carcinoma, endometrioid+secretory adenocarcinoma, mucinous+coloid adenocarcinoma, papillary serous adenocarcinoma+ clear cell carcinoma) (4.24% of all patients, 4.42% of all patients with primary ovarian cancer). All six metastases were represented by carcinomas: one intestinal, one sigmoidian, two with unknown origin and two with several possible primary sites. The mean ages of the patients were 51.66±14.22 years.

Conclusion: The results of our study are similar to those in previous researches regarding the frequency of different histological types and the median age. Ovarian cancer still remains a serious public health issue, thus demanding a well organized screening program.

Keywords: ovarian cancer, ovarian carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, granulosa tumor, disgerminoma, immature teratoma, Sertoli–Leydig tumor, ovarian metastasis, histology, mean age

Introduction

Ovarian cancer has one of the most complex classifications. For a better understanding of our analysis we decided to present the main characteristics of these from the specialty literature.

1. Common epithelial tumors

The current classification of ovarian cancers is published by the WHO [1].

Approximately 90% of ovarian cancers are derived from cells of the coelomic epithelium or modified mesothelium [2] and approximately 75% to 80% of epithelial cancers are of the serous histological type. Less common types are mucinous (10%), endometrioid (10%), clear cell, Brenner, and undifferentiated carcinomas, each of the latter three representing less than 1% of epithelial lesions [3].

Each tumor type has a histological pattern that reproduces the epithelial features of a section of the lower genital tract [4–7].

Nonepithelial malignancies of the ovary account for approximately 10% of all ovarian cancers [8, 9].

2. Sex cord and stromal tumors

Granulosa and stromal cell tumor

Sex-cord-stromal tumors of the ovary account for approximately 5% to 8% of all ovarian malignancies [8–11, 17–21]. This group of ovarian neoplasm is derived from the sex cords and the ovarian stroma or mesenchyme. Granulosastromal- cell tumors include granulosa cell tumors, thecomas and fibromas; granulosa cell tumor is a low-grade malignancy [20–23].

Germ cell tumors

Germ cell tumors are derived from the primordial germ cells of the ovary [8, 9]. Although 20% to 25% of all benign and malignant ovarian neoplasm is of germ cell origin, only some 3% of these tumors are malignant [8]. Teratoma, the most common benign germ cell tumor, accounts for more than 90% of the tumors in this group. Primary malignant germ cell tumors are also uncommon and include dysgerminoma, embryonic carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, and choriocarcinoma. Except for dysgerminoma, all other primary germ cell tumors are high-grade malignancies and are not graded.

The dysgerminoma is the most common malignant germ cell tumor, accounting for approximately 30% to 40% of all ovarian cancers of germ cell origin [9, 12]. The tumors represent only 1% to 3% of all ovarian cancers [8, 11, 13]. The pure immature teratoma accounts for less than 1% of all ovarian cancers, but it is the second most common germ cell malignancy [8].

Endodermal sinus tumors (ESTs) have also been referred to as yolk sac carcinomas because they are derived from the primitive yolk sac [8].

Embryonic carcinoma of the ovary is an extremely rare tumor [14].

Pure nongestational choriocarcinoma of the ovary is an extremely rare tumor [16].

Polyembryoma of the ovary is another extremely rare tumor, which is composed of “embryonic bodies” [8, 12].

Mixed germ cell malignancies of the ovary contain two or more elements of the lesions described above. In one series [15], the most common component of a mixed malig nancy was dysgerminoma. The most frequent combination was a dysgerminoma and an EST.

Sertoli–Leydig tumors

Sertoli-Leydig tumors account for less than 0.2-1% of ovarian cancers [8].

Lipoid cell tumors are thought to arise in adrenal cortical rests that reside in the vicinity of the ovary. More than 100 cases have been reported, and bilateralism has been noted in only a few [8].

Malignant mixed mesodermal sarcomas of the ovary are extremely rare [24–30]. Most lesions are heterologous.

Metastases

Approximately 5% to 6% of ovarian tumors are metastatic from other organs, most frequently from the female genital tract, the breast, or the gastrointestinal tract [31–45]. The Krukenberg tumor, which can account for 30% to 40% of metastatic cancers to the ovaries, arises in the ovarian stroma and has characteristic mucin-filled, signet-ring cells [38, 39].

Rare cases of malignant melanoma metastatic to the ovaries have been reported [46].

Metastatic carcinoid tumors are rare, representing fewer than 2% of metastatic lesions to the ovaries [47].

Lymphomas and leukemia can involve the ovary.

The aim of our study is to assess the frequency of different histological types of ovarian cancers in our hospital over a fifteen year period and to compare the data with the one in literature.

Materials and methods

Our retrospective study concerning the histological types of ovarian cancer covers the 1998–2012 time-span, the data being collected from the Histopathology Exams (HPE) registers. During this time-frame there were 1754 gynecological cancers discovered, out of the total of 22841 histopathological examinations performed, ovarian malignancy being found in 118 cases. The data obtained was compared with similar studies from literature.

Results

During the fifteen year period, a number of 1754 gynecological cancers were diagnosed in our hospital by the anatomopathology department: 1020 cervical cancers (58.15%), 556 uterine cancers (31.70%), 118 ovarian cancers (6.73%), 51 vulvar cancers (2.91%), and 9 vaginal cancers (0.51%). There were 112 cases of primary ovarian cancers (94.92%), five metastases with different origins (4.24%) and a combination thereof (0.85%); in total, 113 patients had primary ovarian cancers (95.76%) and six had metastases (5.08%).

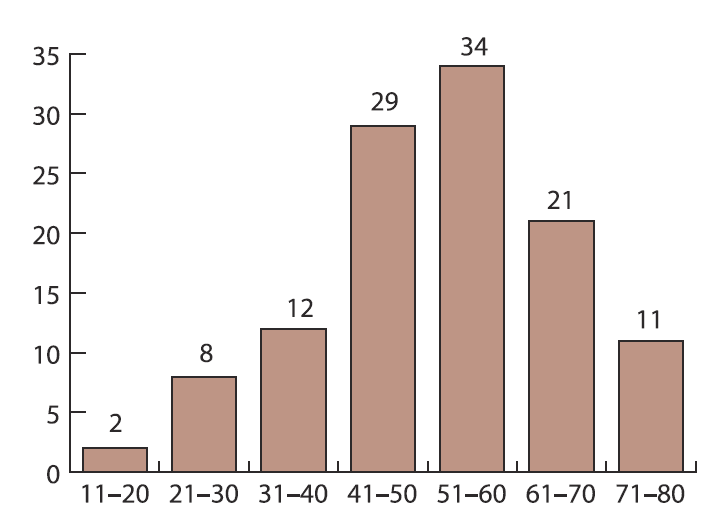

Figure 1 shows the age distribution of the cases; the mean age was 51.66±14.22 years (age range 18–77 years). Table 1 shows the histological types of all the 118 cases of ovarian cancer (metastases are in bold), while table 2 shows the histological types of the 113 cases of primary ovarian cancer (non-carcinoma types in bold), the tumor grading of the primary ovarian cancers and the histological types of the 104 cases of ovarian carcinoma, with adenocarcinoma being present in 84 cases (80.76%); different papillary adenocarcinoma types represented 54 cases of all adenocarcinomas (64.29% of adenocarcinomas, 51.92% of all carcinomas).

| Table 1. Ovarian cancer cases | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cancer type | No. | % |

| Papillary serous adenocarcinoma | 29 | 25.42 |

| Papillary mucinous adenocarcinoma | 18 | 15.25 |

| Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | 10 | 8.47 |

| Clear cell carcinoma | 9 | 7.63 |

| Serous adenocarcinoma | 5 | 4.24 |

| Anaplasic carcinoma/Papillary endometrioid adenocarcinoma | 4 | 3.39 |

| Clear cell adenocarcinoma/Papillary secretory adenocarcinoma/Granulosa cell tumor/Mucinous adenocarcinoma/Disgerminoma | 3 | 2.54 |

| Anaplasic small cell carcinoma/Yolk sac tumor/Papillary adenocarcinoma/Secretory adenocarcinoma/Metastatic carcinoma, unknown origin | 2 | 1.69 |

| Papillary serous adenocarcinoma+ clear cell carcinoma/Endometrioid+secretory adenocarcinoma/Mucinous+coloid adenocarcinoma/Sertoli–Leydig tumor/ Nondiff erentiated carcinoma/Serous carcinoma/Yolk sac tumor+embrional carcinoma/ Immature teratoma with neuroepithelial carcinoma/Immature teratoma/Mature teratoma with squamous epidermoid carcinoma/Immature teratoma with mucinous adenocarcinoma of intestinal metastatic origin/Papillary mucinous adenocarcinoma of sigmoidian metastatic origin/Metastatic carcinoma, unknown origin (gastric, breast, colon)/Metastatic diff use type carcinoma (gastric or breast) +lobular carcinoma | 1 | 0.85 |

Different histological types of carcinoma were detected in 104 cases of the 113 primary cancer cases, who had 118 histological entities (88.16% of the histological types), yolk sac tumors, tumors of the granulosa, immature teratoma, and disgerminoma in three cases each (2.54% each), and Sertoli–Leydig tumors in one case (0.85%). Five (2,56%) had an association of two cancer types (yolk sac tumor with embryonal carcinoma, immature teratoma with neuroepithelial carcinoma, endometrioid+secretory adenocarcinoma, mucinous+coloid adenocarcinoma, papillary serous adenocarcinoma+ clear cell carcinoma) (4.24% of all patients, 4.42% of all patients with primary ovarian cancer). One patient had a simultaneous uterine cancer (0.85%) (Table 2).

| Table 2. Ovarian cancer histological types and grading | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary ovarian cancer type | No. | % of types (118) | % of patients (113) | % of primary carcinomas | G1 | G2 | G3 | N/A | ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||||

| Papillary serous cystadenocarcinoma | 28 | 23.73 | 24.78 | 26.92 | 14 | 50 | 11 | 39.29 | 3 | 10.71 | 0 | 0 |

| Papillary mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | 18 | 15.25 | 15.93 | 17.31 | 8 | 44.4 | 9 | 50 | 1 | 5.56 | 0 | 0 |

| Clear cell carcinoma | 9 | 7.63 | 7.96 | 8.65 | 1 | 11.1 | 4 | 44.45 | 3 | 33.33 | 1 | 11.11 |

| Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | 7 | 5.93 | 6.19 | 6.73 | 2 | 28.57 | 4 | 57.14 | 1 | 14.29 | 0 | 0 |

| Papillary endometrioid adenocarcinoma | 5 | 4.24 | 4.42 | 4.81 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clear cell adenocarcinoma | 4 | 3.39 | 3.54 | 3.85 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 50 | 1 | 25 | 1 | 25 |

| Anaplasic carcinoma | 4 | 2.54 | 2.65 | 2.88 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 75 | 1 | 25 |

| Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | 3 | 2.54 | 2.65 | 2.88 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Endometrioid cystadenocarcinoma | 3 | 2.54 | 2.65 | 2.88 | 2 | 66.67 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33.33 | 0 | 0 |

| Serous cyst-adenocarcinoma | 3 | 2.54 | 2.65 | 2.88 | 1 | 33.33 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 66.67 | 0 | 0 |

| Papillary secretory cystadenocarcinoma | 3 | 2.54 | 2.65 | 2.88 | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Secretory cyst-adenocarcinoma | 3 | 2.54 | 2.65 | 2.88 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Serous adenocarcinoma | 2 | 1.69 | 1.77 | 1.92 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 |

| Papillary serous adenocarcinoma | 2 | 1.69 | 1.77 | 1.92 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anaplasic small cell carcinoma | 2 | 1.69 | 1.77 | 1.92 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 |

| Papillary cystadenocarcinoma | 2 | 1.69 | 1.77 | 1.92 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | 1 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Serous carcinoma | 1 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Squamous epidermoid carcinoma | 1 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 1 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| Neuroepithelial carcinoma | 1 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Colloid adenocarcinoma | 1 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| Yolk sac tumor | 3 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 |

| Granulosa cell tumor | 3 | 2.54 | 2.65 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 |

| Disgerminoma | 3 | 2.54 | 2.65 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 |

| Immature teratoma | 3 | 2.54 | 2.65 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 |

| Sertoli–Leydig tumor | 1 | 2.54 | 2.65 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| Embryonal carcinoma | 1 | 0.85 | 0.88 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

The SEER database (48) shows the following distribution of the histological types (Table 3).

Metastases represented 5.08% versus 5-6% in literature [31–45].

Several ovarian cancer histological types in our study are similar or close to those in literature, the differences being partially explained by the relatively small number of cases in our study.

| Table 3. Comparison between our studies results and SEER database | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histology (48) | All Races | Present study | Other (2), (8), (11), (13) | |

| Count | Percent | |||

| Carcinoma | 22,533 | 92.1% | 88.16% | 90% |

| Epidermoid carcinoma | 177 | 0.7% | 0.85% | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 20,671 | 84.5% | 72.03% | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 3,223 | 13,2% | ||

| Papillary adenocarcinoma | 531 | 2.2% | 1.69% | |

| Clear cell adenocarcinoma | 1,263 | 5.2% | 3.39% | |

| Endometrioid carcinoma | 2,479 | 10.1% | 12.71% | |

| Cystadenocarcinoma | 143 | 0.6% | ||

| Serous cystadenocarcinoma | 3,490 | 14.3% | 2.54% | |

| Papillary serous cystadenocarcinoma | 6,840 | 28.0% | 23.73% | |

| Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | 519 | 2.1% | 2.54% | |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 880 | 3.6% | 0.85% | |

| Mucin-producing adenocarcinoma | 75 | 0.3% | ||

| Other adenocarcinoma | 1,228 | 5.0% | ||

| Anaplasic carcinoma | 5.08% | 5% | ||

| Other specific carcinomas | 544 | 2.2% | 2.54% | |

| Stromal cell tumor | 327 | 1.3% | 2.54% | |

| Other | 217 | 0.9% | ||

| Sertoli–Leydig tumor | 2.54% | 0.2-1% | ||

| Dysgerminoma | 2.54% | 1-3% | ||

| Unspecified, Carcinoma | 1,141 | 4.7% | ||

| Sarcoma and other soft tissue tumors | 87 | 0.4% | ||

| Other specific types | 1,629 | 6.7% | ||

| Mullerian mixed tumor | 697 | 2.9% | ||

| Teratoma, malignant | 358 | 1.5% | 2.54% | |

| Other | 574 | 2.3% | ||

| Unspecified | 206 | 0.8% | ||

| Total | 24,455 | 100% | ||

Conclusions

Ovarian cancer, although less frequent than other gynecological cancers, is usually diagnosed in advanced stages due to the non-specific signs and symptoms, which lead to many errors in interpreting them and to undesired delays in diagnosis and treatment, and to the lack of an organized and well conducted screening program. Due to the cost of biochemical screening, as FIGO also suggest, we find inappropriate a national screening program using CA 125, but including a transvaginal ultrasound examination in a yearly based control program can help identifying high risk patients. The use of ROMA score could be assessed in comparison to the use of only CA 125, increasing both sensitivity and specificity in high risk patients. CT scan and MRI should be used in suspicious ultrasound results.

Arad County has the second highest cancer incidence in Romania after Bucharest. The age of discovering ovarian cancer (51.6 year) can be considered significantly lower than the international mean (~60 year), although the rates of different ovarian histological types of cancer is very similar to the international databases (SEER). This particularity can be a point of further research in the Euro region.

References

- Young RH. A brief history of the pathology of the gonads. Mod Pathol 2005; 18(Suppl 2): S3.

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Murray T, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, et al. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin 2009; published online. doi:10.3322/caac.20006.

- Scully RE, Young RH, Clement PB. Tumors of the ovary, maldeveloped gonads, fallopian tube, and broad ligament. In: Atlas of tumor pathology, 3rd Series, Fascicle 23. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1998. p. 1–168.

- Kindelberger DW, Lee Y, Miron A, Hirsch MS, Feltmate C, Medeiros F, et al. Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: Evidence for a causal relationship. Am J Surg Pathol 2007; 31: 161–169.

- Callahan MJ, Crum CP, Medeiros F, Kindelberger DW, Elvin JA, Garber JE, et al. Primary fallopian tube malignancies in BRCA-positive women undergoing surgery for ovarian cancer risk reduction. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 3985–3990.

- Carlson JW, Miron A, Jarboe EA, Parast MM, Hirsch MS, Lee Y, et al. Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: its potential role in primary peritoneal serous carcinoma and serous cancer prevention. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 4160–4165.

- Levanon K, Crum C, Drapkin R. New insights into the pathogenesis of serous ovarian cancer and its clinical impact. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 5284–93.

- Scully RE, Young RH, Clement RB. Tumors of the ovary, maldeveloped gonads, fallopian tube, and broad ligament. In: Atlas of tumor pathology: 3rd series, Fascicle 23. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1998. p. 169–498.

- Chen LM, Berek JS. Ovarian and fallopian tubes. In: Haskell CM, ed. Cancer treatment, 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000. p. 900–932.

- Imai A, Furui T, Tamaya T. Gynecologic tumors and symptoms in childhood and adolescence: 10-years’ experience. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1994; 45: 227–234.

- Gershenson DM. Management of early ovarian cancer: germ cell and sex-cord stromal tumors. Gynecol Oncol 1994; 55: S62–S72.

- Kurman RJ, Scardino PT, Waldmann TA, Javadpour N, Norris HJ. Malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary and testis: an immunohistologic study of 69 cases. Ann Clin Lab Sci 1979; 9: 462–466.

- Obata NH, Nakashima N, Kawai M, Nikkawa F, Mamba S, Tomoda Y. Goandoblastoma with dysgerminoma in one ovary and gonadoblastoma with dysgerminoma and yolk sac tumor in the contralateral ovary in a girl with 46XX karyotype. Gynecol Oncol 1995; 58: 124–128.

- Ueda G, Abe Y, Yoshida M, Fujiwara T. Embryonal carcinoma of the ovary: a sixyear survival. Gynecol Oncol 1990; 31: 287–292.

- Tay SK, Tan LK. Experience of a 2-day BEP regimen in postsurgical adjuvant chemotherapy of ovarian germ cell tumors. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2000; 10: 13–18.

- Simosek T, Trak B, Thnoc M, Karaveli S, Uner M, Seonmez C. Primary pure choriocarcinoma of the ovary in reproductive ages: a case report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 1998; 19: 284–286.

- Young RE, Scully RE. Ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors: problems in differential diagnosis. Ann Pathol 1988; 23: 237–296.

- Miller BE, Barron BA, Wan JY, Delmore JE, Silva EG, Gershenson DM. Prognostic factors in adult granulosa cell tumor of the ovary. Cancer 1997; 79: 1951–1955.

- Malmström H, Högberg T, Risberg B, Simonsen E. Granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: prognostic factors and outcome. Gynecol Oncol 1994; 52: 50–55.

- Segal R, DePetrillo AD, Thomas G. Clinical review of adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol 1995; 56: 338–344.

- Cronje HS, Niemand I, Barn, RH, Woodruff JD. Review of the granulosa-theca cell tumors from the Emil Novak ovarian tumor registry. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999; 180: 323–328.

- Aboud E. A review of granulosa cell tumours and thecomas of the ovary. Arch Gynecol Obstet 1997; 259: 161–165.

- Young R, Clement PB, Scully RE. The ovary. In: Sternberg SS, ed. Diagnostic surgical pathology. New York: Raven Press, 1989:1687.

- Le T, Krepart GV, Lotocki RJ, Heywood MS. Malignant mixed mesodermal ovarian tumor treatment and prognosis: a 20-year experience. Gynecol Oncol 1997; 65: 237–240.

- Piura B, Rabinovich A, Yanai-Inbar I, Cohen Y, Glezerman M. Primary sarcoma of the ovary: report of five cases and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 1998; 19: 257–261.

- Topuz E, Eralp Y, Aydiner A, Saip P, Tas F, Yavuz E, et al. The role of chemotherapy in malignant mixed müllerian tumors of the female genital tract. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2001; 22: 469–472.

- van Rijswijk RE, Tognon G, Burger CW, Baak JP, Kenemans P, Vermorken JB. The effect of chemotherapy on the different components of advanced carcinosarcomas (malignant mixed mesodermal tumors) of the female genital tract. Int J Gynecol Cancer 1994; 4: 52–60.

- Berek JS, Hacker NF. Sarcomas of the female genital tract. In: Eilber FR, Morton DL, Sondak VK, Economou JS, eds. The soft tissue sarcomas. Orlando, FL: Grune & Stratton; 1987. p. 229–238.

- Barakat RR, Rubin SC, Wong G, Saigo PE, Markman M, Hoskins WJ. Mixed mesodermal tumor of the ovary: analysis of prognostic factors in 31 cases. Obstet Gynecol 1992; 80: 660–664.

- Fowler JM, Nathan L, Nieberg RK, Berek JS. Mixed mesodermal sarcoma of the ovary in a young patient. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reproduc Biol 1996; 65: 249–253.

- Petru E, Pickel H, Heydarfadai M, Lahousen M, Haas J, Schaider H, et al. Nongenital cancers metastatic to the ovary. Gynecol Oncol 1992; 44: 83–86.

- Demopoulos RI, Touger L, Dubin N. Secondary ovarian carcinoma: a clinical and pathological evaluation. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1987; 6: 166–175.

- Young RH, Scully RE. Metastatic tumors in the ovary: a problemoriented approach and review of the recent literature. Semin Diagn Pathol 1991; 8: 250–276.

- Moore RG, Chung M, Granai CO, Gajewski W, Steinhoff MM. Incidence of metastasis to the ovaries from nongenital tract tumors. Gynecol Oncol 2004; 93: 87–91.

- Ayhan A, Tuncer ZS, Bukulmez O. Malignant tumors metastatic to the ovaries. J Surg Oncol 1995; 60: 268–276.

- Curtin JP, Barakat RR, Hoskins WJ. Ovarian disease in women with breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol 1994; 84: 449–452.

- Yada-Hashimoto N, Yamamoto T, Kamiura S, Seino H, Ohira H, Sawai K, et al. Metastatic ovarian tumors: a review of 64 cases. Gynecol Oncol 2003; 89: 314–317.

- Kim HK, Heo DS, Bang YJ, Kim NK. Prognostic factors of Krukenberg’s tumor. Gynecol Oncol 2001; 82: 105–109.

- Yakushiji M, Tazaki T, Nishimura H, Kato T. Krukenberg tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic analysis of 112 cases. Acta Obstet Gynaecol Jpn 1987; 39: 479–485.

- Misdraji J, Yantiss RK, Graeme-Cook FM, Balis UJ, Young RH. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a clinicopathologic analysis of 107 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2003; 27: 1089–1103.

- Chou YY, Jeng YM, Kao HL, Chen T, Mao TL, Lin MC. Differentiation of ovarian mucinous carci-noma and metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma by immunostaining with beta-catenin. Histopathology 2003; 43: 151–156.

- Seidman JD, Kurman RJ, Ronnett BM. Primary and metastatic mucinous adenocarcinomas in the ovaries: incidence in routine practice with a new approach to improve intraoperative diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol 2003; 27: 985–993.

- Lee KR, Young RH. The distinction between primary and metastatic mucinous carcinomas of the ovary: gross and histologic findings in 50 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2003; 27: 281–292.

- McBroom JW, Parker MF, Krivak TC, Rose GS, Crothers B. Primary appendiceal malignancy mimicking advanced stage ovarian carcinoma: a case series. Gynecol Oncol 2000; 78: 388–390.

- Schofield A, Pitt J, Biring G, Dawson PM. Oophorectomy in primary colorectal cancer. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2001; 83: 81–84.

- Young RH, Scully RE. Malignant melanoma metastatic to the ovary: a clinicopathologic analysis of 20 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1991; 15: 849–860.

- Motoyama T, Katayama Y, Watanabe H, Okazaki E, Shibuya H. Functioning ovarian carcinoids induce severe constipation. Cancer 1991; 70: 513–518.

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, Edwards BK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2008, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008/, based on November 2010 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2011.

Download Full Article

- Furău Gheorghe: Histological types of ovarian cancer in Arad county: a fifteen years retrospective analysis (2016, Journal of Hungarian Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, PDF, 6 pages, English, 212KB)